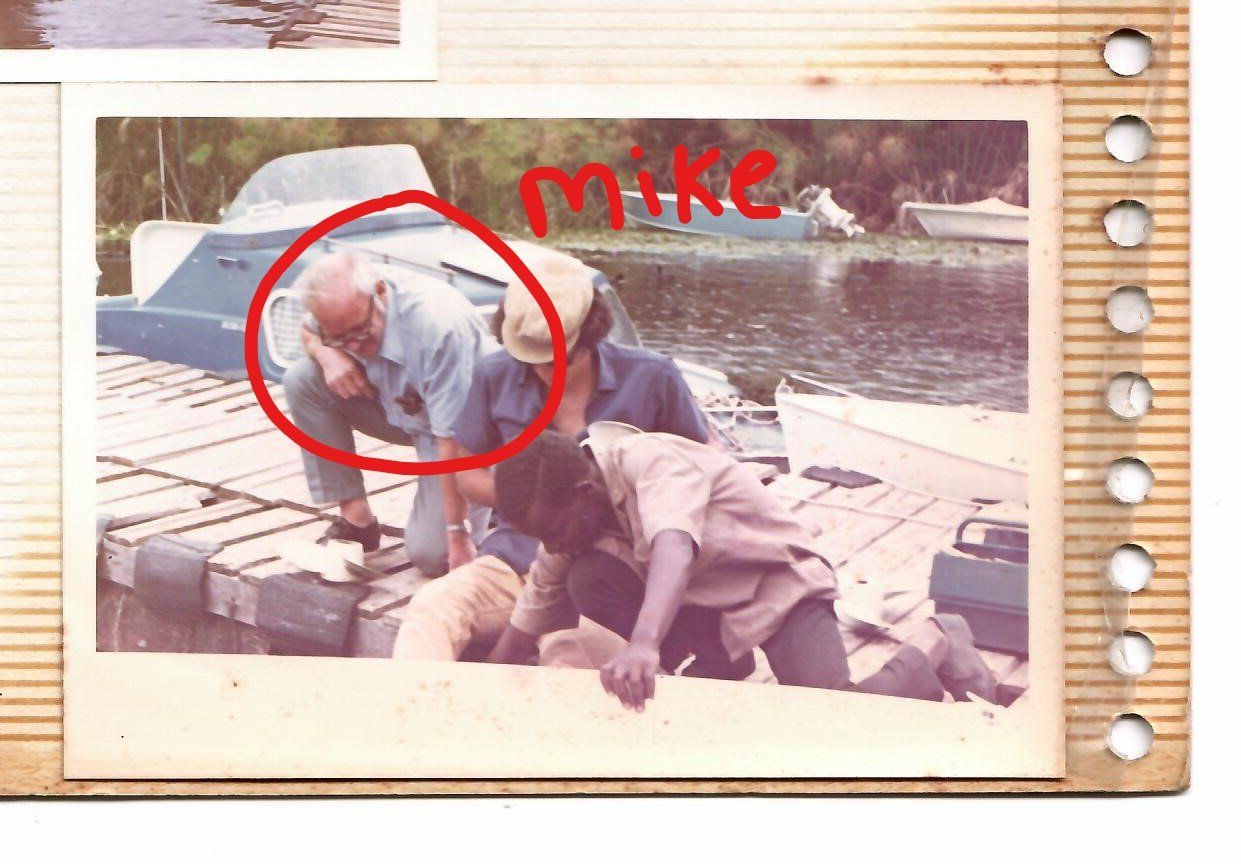

Mike Richmond was a Pedophile

The call came in at 3pm over the satellite phone, the shrill ring erupting in the liquid heat of mid-afternoon. It was from Nairobi, the manager of a plane charter company. I could just make her out through the staticky connection: “They told us they were stuck in the mud and were going to walk to the nearest village. But it’s been six hours and we haven’t heard anything. Night is coming. We are worried.”

A week before, a learner pilot had crashed a single engine plane at the bush strip 30 miles north of us. Wosiwosi was a desolate place, a string of huts on a high, over-grazed plateau above Lake Natron in northern Tanzania. The local Masai had saved the pilot’s life, giving him water and food until a rescue plane flew in and retrieved him. His plane, however, was still in Wosi, nose gently nudging a termite mound just off the strip.

This second team, the manager said, included the plane company’s owner, his mechanic and a driver. They had come to assess the plane’s damage and, if they couldn’t fly it, figure out how to get it back to Nairobi on the rough track that edged uncertainly along the lake shore over razor sharp volcanic rock and through the viscous lake mud. It was this mud in which they were now stuck. “Can you help?”

I hesitated. It was late to drive to Wosi, at least an hour away on what was little more than a cow path through lion-filled wilderness. Apart from the cook I was alone in camp. I didn’t want to break down or get stuck myself.

My husband, Matt Aeberhard, was back in London, editing the film we were making for NatureDisney – The Crimson Wing: Mystery of the Flamingos. We had lived here, in an abandoned missionary’s house, on the wild edge of Lake Natron, for three years. Natron is about half way between Mt. Kilimanjaro and Serengeti National Park, on the floor of the Great Rift Valley. But casual map readers cannot comprehend the remoteness – the swooping geology of Gelai and Ketumbeine mountains as they descend in the east to the plains and the lake. The Rift, to the west, surges up from the lake, a geological tidal wave, peaking in the dark, jagged silhouette of Masonik. Distance expands under the high arc of the equatorial sky. You are forced to travel slowly, either by foot or a beetle’s pace in a car, and so the landscape unfolds incrementallyqa like some exquisite origami. I am certain that I absorbed the vision of Natron in a different way because of how I moved within its rills and creases and vertiginous space. Even now, I can close my eyes and see exactly the rough track to our village. I know each tree and the individual rocks we used as markers when the rains washed away any trace of our route. Memory has needed no embellishment.

The village of Magadini where we lived was 100 miles from the nearest electric light – a five hour drive on the best of days, through vales of fine, obscuring dust, up to the car’s axel. In the rainy season, the dust was mud, and it was possible to be stuck for days before anyone else came along. There were often rumors of bandits hiding in the man-high yellow grass on the way. And there were bored Masai boys who threw rocks at passing cars and then, laughing, vanished into another dimension of scrub thorn.

Lake Natron, the centerpiece of this Tolkienesque geology, is shallow and entropic and so toxic with evaporated salt that nothing can survive in its waters – except millions of Greater and Lesser Flamingos who feed on the algae blooms and breed in voluptuous numbers. As the Rift is still separating, the earth here moves and shifts in earthquakes; sinkholes appear overnight on the mudflats; the hot springs on the lake edge gurgle and almost boil. At that time, 2008, the sharp spire of the active volcano, Ol Donyo Lengai was still spewing smoke and lava from an eruption the year before. The land itself seemed alive under us, like a sleepy dragon.

Our filming work was physically tough in the heat and the salty stink of the lake, and there was no real respite in camp, as we’d become an impromptu medic station for the local community. I had the only first aid kit for many miles plus very basic wilderness medicine knowledge. Each day, sick and wounded Masai trooped up the hill. Most of my work was triage, but I learned how to clean and dress burns, how to diagnose TB of the spine and detect pre-eclampsia in pregnant women – a lethal condition treatable only by caesarian delivery of the baby in a hospital.

I recognized that this time in my life was exceptional. I felt sharp and bright, clearly delineated, and I never, for a moment, wanted to be anywhere else. I did not miss luxury or art or friends or restaurants. Here, here, here, on the shore of Lake Natron, on this dragon’s back, I was intensely present. Most of my adult life I’d vacillated between being insecure and ineffective – a pretty, restless fool - and being deeply self-destructive. The self-destruction was a vocation: I took it seriously, working my way through two decades of drugs, booze, self harm and bad men. A brilliant therapist in New Mexico had set me on a different course and by the time I got to Natron I was married to a man I loved and writing a film with him. In that splendid isolation, I began to reinvent myself as a competent person. And so, that afternoon, I threw a box of bottled water and a half-dozen electrolyte sachets into the back of the Land Rover, and headed north to Wosi.

The track dipped into narrow, dry korongos and crabbed perilously over rocky cliffs. I veered around the carcass of a zebra left by over-fed lions the night before. There were no tire tracks but mine. The lake, to my left, was slick in the lowering light, so perfect a reflection of the sky that migrating birds often crashed into it, unable to differentiate between the elements of air and water.

By 4:30, I was at the airstrip in Wosi. Huddled in the shade of a lonely bush, I found two men – an old white guy in shorts and knee socks, and a tall Kenyan in jeans and sunglasses. They were in equal measure relieved, exhausted and scared. Colin, the company’s owner, and Jeff, his driver, introduced themselves between gulps of water. They told me they’d decided not to carry a lot of water because it was too heavy, and they’d misjudged the distance between their vehicle and the airstrip. Seven nautical miles didn’t seem far when they’d set out, but the land here was lumpy, rough, rocky and crowned with spikey, prickly, stabby plants. Colin then told me they’d left the third man about halfway back. He’d been succumbing to heat-stroke. They’d made him climb a tree to avoid the lions and hyenas.

A small crowd of Masai children soon appeared to join us. They were tending their beautiful tame cows in the long grass buffering the airstrip. One of them knew exactly where Colin and Jeff had stashed their mate. This was their neighborhood, where they ranged with their livestock each day, from dawn ‘til dusk with only their goats’ milk for sustenance. No matter where I stopped, no matter how far I was from the nearest village, such ragged, sinewy children would appear and stare. Closer to civilization, they had learned to beg. But here they smiled and giggled, for we were fabulous entertainment; we were a circus with clowns and jugglers and prancing horses.

A boy climbed into the Landie with us, giving perfect directions. The drive was harrowing – steep drops over axel-torqueing rocks. It was nearly dark when we arrived at the tree and helped Sam down. He was barely conscious, babbling incoherently. We got the water into him, slowly, consistently. On the way back to our camp, we stopped at the hot springs to soak his clothes. The water wasn’t cold, but the dampness with the minor breeze coming in the open car window was better than just the day’s stubborn heat.

That night, while a rehydrated Sam slept, Colin and Jeff joined me for dinner of beans and rice. “You saved our lives,” Colin said. I demurred: the Masai of Wosiwosi would have taken care of them. But Sam? Yes, it’s likely I saved Sam simply by showing up with clean water and rehydrants. Because I had a phone, a car and rudimentary medical knowledge, saving people had become my super power. The Masai were accustomed to surrendering to God’s will – Shauri ya Mungu. If they were too sick to walk the three days to the good doctor on the other side of Gelai Mountain: Shauri ya Mungu, they died in their huts. If they walked to the bad doctor in Engaresero and he was drunk or had no medicines: Shauri ya Mungu.

I hadn’t set myself up as a “doctor” – I was a writer. I had no training in triage or the terrible consequences of a wrong decision. One evening a young mother – perhaps 15 or 16 - walked up the drive with her grandmother. They wore many layers of beads, reflecting their respect for me and the seriousness of their situation. Reaching me, the girl unwrapped her robes to reveal her beautiful baby. The infant was very sick and in obvious pain. I judged it was too late to send them out in the car, for we’d heard the bandits were active. On advice from my mother-in-law, Penny, a GP in the UK, I gave the baby some antibiotics. We kept the trio through the night, urging the mother to keep giving her baby milk and water by spoon as she was too weak to suckle. At daybreak, we sent them off with the driver. By noon, I heard back from the clinic: the baby had died of massive organ failure soon after her arrival. It turned out that she had not been suckling well for a few weeks and so the grandmother had given her some “bush medicine” – roots or leaves, the myriad of traditional medicines, many of which were powerful emetics. It was this, in toxic proportions, which had killed the baby.

The two women returned that evening. The young mother’s arms, having grown used to the weight of her child, hung useless by her side. Shauri ya Mungu, the grandmother said. But it wasn’t anything to do with God. It was her fault for giving the baby too much medicine, and it was my fault for not sending the driver out at night. He would have agreed, he would have braved the dangerous night to save a child if I had only asked. Instead of guilt or sorrow or anger, however, I felt nothing. This strange blankness affected me even when I saved a life. The saving felt lucky, I’d turned left instead of right. I began to question the whole decision-making process. Practicing medicine is pretty mechanical: it’s not magic, it’s not even intuitive. I was more of a traffic cop than a shaman. Much of the time whether someone lived or died depended on unknowable factors. I had a pregnant woman with a hemoglobin count of four who walked for eight hours in 90F heat to reach me. Her blood was basically water. Why on earth was she still alive?

Over time, I came to understand Shauri ya Mungu existentially: caught in the net of ourselves and our circumstances – that ineffable, infinite matrix of chance - we don’t decide so much as we default. Free will is a Western invention: the fetishized belief that an individual must swim against the current of fate in a life-long act of self-improvement. It’s an idea created by people who have actual options – though I still wonder about the psychological mechanisms that allow us to act on them.

Jeff went off to bed. Colin remained with me on the verandah. He’d had a shower. He’d even cleaned his socks and they’d already dried in the night’s convection oven heat. He told me that he ran his small plane charter business out of Wilson Airport, the municipal airport in Nairobi. The pilot who’d crashed had actually been aiming for Lake Magadi a hundred miles north. “Bloody idiot!”

I knew Wilson Airport well. Memories strung out behind the name like bunting. My father had kept a small plane there, and I’d flown with him as a child. A fighter pilot in the Pacific in World War II, he was traumatized and alcoholic, yet he still loved to fly – slipping those surly bonds of earth with its domestic demons. Very occasionally, he’d asked me to join him, just the two of us striking out at dawn. I remember the cold on my bare legs and the smell of airplanes – fuel and rubber. He’d bring extra cushions for me to sit in the co-pilot’s seat. “Clear!” He’d yell and start Cessna’s engine, the propeller furiously whisking the air. He’d fly low over the Athi River and we’d see a pride of lions lounging on a sand bank; or he’d bank north, circle the spire of Mt. Kenya, skim the Aberdare Forest and surprise me with the drop of a gigantic waterfall. I did not dare speak to him, afraid to break the rare communion, afraid he’d turn either violent or melancholic.

My father drank at many places. One of them was the Aeroclub, at the west end of Wilson. Though the Aeroclub had a small, slimy pool and a restaurant for families, it was primarily a watering hole for pilots. Every aviator at Wilson drank at the Aeroclub. In those days – the 1960s and to mid-70s - no one seemed concerned about drunk men getting into planes and flying them. It was the same with driving, with seatbelts, with wife-beating, with adultery, with hunting. Men – white men – could still do what they liked in that first decade of post-colonial Kenya. They didn’t belong to some secret club, they weren’t rich or in positions of political power. Their power was social, historical, genetic: customary. They were all little Lords. And yet, how many of that generation were like my father – broken or twisted by the war in ways that were not acknowledged, let alone treated?

Their families were dragged into the slipstream of their messy lives, and we accepted this lawlessness and immorality, this cruelty and selfishness and alcoholism as perfectly normal behavior. At my school, the Banda Preparatory, we had a Latin teacher with one eye, Mr. Japson. He’d lost the other eye in war, and had it replaced with an ill-fitting glass one. When he was possessed by sudden fits of rage, the fake eye would jiggle violently in its socket. We would watch the eye carefully, certain that one day it would pop out and roll across the floor like a marble and then we’d be able to see right into Mr. Jap’s skull. One day, Mr. Jap picked up Quentin Smith, still in his desk, and threw the boy and the desk out the door. No one complained, not even his parents. We carried on with our Latin vocab.

Among my father’s friends at the Aeroclub was Mike Richmond. Even now, five decades later, his name and the specific set of memories it triggers is like finding a centipede in the shower. I feel revulsion and fear. Sweat prickles in my armpits. Mike Richmond was a pedophile. He was a prolific pedophile. He was also the Chairman of the Aeroclub. He was my father’s best friend. He came over on Sundays for lunch, and after lunch when my mother and father went for a nap, he would take me into the spare bedroom with a copy of “Winnie the Pooh” he had no intention of reading.

In those lonely, interminable Sunday afternoons, Mike seemed to want to please me. He would ask, “Does this feel good?” I knew I was supposed to say, “Yes,” in the way I should say “Yes” when being served boiled tongue and turnips by my grandmother. The “No” was yelling in my head, but what came out of my mouth was the response I knew he expected: “Yes.”

This went on for years, from aged four until eight or nine, when he did it to my best friend, Vanessa, while she was over for a playdate. He had us in bed on either side of him. Ness went home and immediately told her parents. I recall hushed discussions between our parents, but no direct examination – no effort to ask me what, exactly, had happened and was I all right. I had a sense of my mother’s embarrassment, of her inability to understand what she must do – or could do - in response. Mike no longer came to lunch. But he was still there, at the club, around, chatting and laughing. Drinking with my father.

What this reaction tells you as a child, alert to adult signals, is that it is perfectly OK for a man to put his fingers into your six-year-old vagina. It is normal. All your own deeply instinctive feelings of disgust, unease, fear, violation and even physical pain are incorrect. You are wrong to feel them. Lacking any other means to navigate this emotional cauldron, I deferred to my manners – that bourgeois code of behavior drilled into me from an early age. Put your napkin on your lap. Keep your elbows off the table. Refer to the loo never the toilet. Children should be seen and not heard. This last rule was especially important, I knew, for I often crept past my father as he slept in his chair in the corner of the living room, a glass of whisky gripped fast in his fist, the ice long melted.

Fifteen years later, in 1990, I was back in Kenya, working as a freelance journalist – a piece about elephant poaching for the Sydney Morning Herald. My interview subject asked me to meet him at the Aeroclub bar. Nothing had changed at the club. The same bougainvillea ambushed the parking lot. The pool – in which my younger brother had once copiously crapped - was still suspiciously green. The wood paneled interior – a long low room with windows on the east side – still had flying paraphernalia on the walls. The bar, however, had been expanded. Once a small, dark cubbyhole, it was now an airy space. At some point, during the interview, I went to the Ladies. Along the walls of the dining room were plaques bearing the names of all the club’s Chairmen. I wasn’t looking, just glancing casually as I walked. And there it was, Mike Richmond, Chairman from 1972 to 1989.

I had not forgotten what he had done. But neither had I considered it. The Sundays were embedded within me so deeply, like every other childhood memory, including the good ones. I’d had no reason dig within the dark earth of the past – who would choose to? It was like a mental “Omerta.” I had not summoned the centipede. Yet it came crawling out, fat and quick.

Without thinking, I asked a passing waiter, “Do you know Mike Richmond?”

“Yes, yes. He’s there. That table.”

And he was. There. Eating chicken. I recognized him instantly.

I was shaking, flushed, but strangely elated. Before I could think things through, I went over to him. “Hello,” I said. “I’m Melanie. Ian Leslie’s daughter.”

He smiled, as if delighted. “Oh? Ian’s daughter! Yes! Hello!”

“I need to speak with you. Urgently.”

He made an apology to his lunch guests. In the lobby, he put his hand on my arm.

“Don’t touch me.” I snatched myself away from him. “I know what you did to me. I remember. I know what you did to other girls.”

For the briefest moment, he looked uneasy. Then he gave me a smile, like a boy caught stealing a sticky bun – no: like a man imitating a boy caught stealing a sticky bun. The guilt was shallow and artificial. “That. Oh, that.”

The that of that stuck to me, not him – the filth of it, the specific memories, the way I’d walked calmly up the stairs to the guestroom where he’d waited with Pooh and Piglet. I never said a word to my parents. It hadn’t even occurred to me to tell them. He must have guessed that I wouldn’t, and the longer it went on without me telling anyone, the bolder he had become with my body. “Does this feel good?” Mike had imagined we were equals, six-year-old me and hairy, balding him: Does this feel good? It was how he straightened things out in his sick head. He had spoken to me as one adult to another, as lovers, ensuring my complicity. For what child doesn’t want to be treated as a grown-up?

I was not a child anymore, I was an angry young woman. My anger took many forms, mostly as a weapon I turned against myself. Yet, right then, it was solid, cold and sharp in my hand. I looked at his bland face, the watery blue eyes, the burst veins splotching his nose, and I felt powerful. “If I ever hear you’ve touched another child I swear I will get a knife and stab you to death.”

I believed – I believe – I would.

Walking away, back to my interview, I was amazed that I could switch on and off, from the violent threat that I meant with every cell in my body, to attendant journalist asking about elephant poaching. Later, I also wondered why I’d been so polite to Mike in front of his guests. Why didn’t I just unload on him there, publically out him? You disgusting pedo, you filthy pedo. Then I saw the familiar pattern: how much I did not want to offend or make a fuss. I wanted to be polite. Omerta.

Mike abused dozens of little white girls in the small social scene of Nairobi in the sixties and seventies. Who knows how many little black girls? And maybe boys, too. He was always “babysitting.” He was always around families with children. When my mother left my father and re-married in 1976, she saw Mike once again at the Aeroclub with a newly arrived family – a mum and dad and two daughters, all white and pink like other jet-fresh English people. My mother hurried away: “I didn’t know what to tell them.” Yet, she herself had been warned about Mike as he slithered into our dysfunctional home when I was two years out of diapers. People knew. Mothers knew. Fathers knew. The knowing was like a fog – a malarial miasma. But Mike was still Chairman until 1989. The club nabobs had even let him operate a children’s photography business on the grounds.

In 2000, I was back in Nairobi and once again meeting someone at the Aeroclub. As I parked my car, I noticed there was a new guest annex. Very nice, I thought, so if you were too drunk to fly or drive, you could crash out rather than just crash. On the side of the building I saw a shiny brass plaque: Built with a bequest from our dear friend Mike Richmond.

That night, I wrote a letter to the Chairman of the Aeroclub, Harry Trempenau (as I haven’t kept any of our correspondence, I paraphrase all our correspondence from memory): This man was a pedophile, he abused me and he abused many other young children. How dare you erect a plaque in his honor? If you do not take it down I will write an expose about him and how you have all sheltered him for the past thirty years.

Some months later, a reply came from Mr. Trempenau. If what I said was true, he challenged, why I was only now coming forward? My response was short and angry: Because I was eight years old when I’d been abused. Responsible adults, possibly you among them, Mr. Trempenau, did nothing to protect me or his other victims. Take down the plaque. It’s a disgrace, it spits in our faces. The least you can do is get out a screwdriver.

Mr. Trempenau never responded. But I heard from my friend Ness that the plaque was removed.

Less than a decade had passed between those letters and Colin’s unexpected arrival in my life. Dark, silent miles padded us from the outer world. Beyond the thorn fence encircling the house, wild animals moved on silent hooves, and the flamingos honked softly out in the middle of the lake. A kerosene lantern fixed us to this particular place and time, this single point of light that shone from the hillside across the lake, the beacon to a lone villager walking home across the mud flats. I did not know Colin, I cannot claim I had some instinct about him. He was a just a nice man in white socks who’d made a bad decision that had nearly been a fatal one. Yet how much had to align for he and I to meet: the billions of years of geology, the climate, the weather, the human history, the personal history, the missionary who built the house, the man I met in a bar in Arusha and married, the producer who’d green lit our film, the bloody idiot pilot who crashed the plane, the satellite spinning overhead that carried Colin’s manager’s voice to mine, the technicians who’d designed the satellite, the crew who’d catapulted it up there into space.

The writer in me has an ambivalent, slightly fearful attitude about our meeting. The universe had worked so hard to draw us together: surely, there must be some profound denouement – a reckoning. On the other hand, how lazy – how perfunctory the coincidence. A reader should never believe such a Deus ex Machina in fiction let alone autobiography.

In the middle of our conversation – an immemorial scroll of chat - Colin suddenly said my name: “Melanie Finn! Melanie Finn!”

He pointed his finger at me, his eyes bright, as if he’d suddenly figured out a crossword clue that had eluded him for years. “You wrote those letters!”

Those letters.

I tuned in to hear the intonation – the casual discard: That, oh that. But I could not detect it.

“I was on the Board,” Colin went on, animated. “We read your letters. You should know that. Some of us admitted that we’d known about Mike. It was difficult to talk about it. Some of our own daughters, some of us -” He faltered. “One of the Palmerson’s daughters killed herself.”

Should this be enough for me? To know I was heard? To know I was right? That there was regret, recognition of the tragic consequences of their collective failure to lift a finger? That the fucking plaque had been taken down not because I demanded it but because those men felt some shame? Perhaps I’d get an apology, a real one: I’m sorry, we’re sorry..

"He died, you know. Stomach cancer.” Colin looked at me directly after he’d said this. “It was messy. You mustn’t think he deserved it.”

But I did. I thought it lavishly in the light speed between his words. I wanted Mike Richmond to have suffered, oh yes, tubes in his body, sitting in his own shit, rotting slowly from the inside, in pain, alone, stinking like old compost. My thoughts were like warm, dark truffles. He deserved stomach cancer because Susie Palmerson had died of the wounds he’d made in her and no one had cut his balls and left him to bleed to death in a ditch. Instead, they’d put up a plaque.

The problem for writers is when real things happen to us – extraordinary events, such coincidences as this - we try to impose structure and form and plot, we move facts around so there will be the beginning, the middle, the end. We train ourselves to emotional revelation. We love pattern, we love irony, we construct theme. Characters evolve, conflicts resolve. Even as Colin sat there with me, drinking warm beer in the African night, I wanted to feel I was at last making sense of my childhood – that I could understand the people who enabled Mike Richmond. Their complicity would suddenly make sense to me. Or that I’d find some sympathy for Mike in the manner of this death. I wanted so much to feel a momentous shift – a release, a forgiveness, cathedral bells ringing. I wanted to be the heroine of my story. I wanted to become a changed person.

Yet there was nothing, I felt nothing. Nothing beyond the fact of me and Colin and the lantern and the night. The past is as immovable as geology, you just bash your head against it. As a reader who has followed me this far, you’re expecting more - aren’t you? For the act of writing is a contract, I’m supposed to deliver to you some truth or insight. But I am not any wiser than you. I could find no meaning in my collision with Colin. All I can tell you is that the abused never recover, we never walk free of what was done to our bodies and our little silver souls. We can never understand why we were abandoned every Sunday afternoon, why even reasonable adults, loving parents, were not paying more attention, they did not protect us or rescue us, and they did not punish the wicked. We can write and write and write, so many stories with so many different endings, but we can never change our own outcomes, we will not find the sense, there is no absolution. We are still stuck with exactly who we are. Yet that self expands as we move through life – if we are lucky enough to live; and I find that I am filled more and more with the memory of Natron’s stark beauty and with the morning kisses of my children and the eager smile of my old dog and the pile of dishes in our kitchen sink and the phone call from a friend urging me to join her on a walk. And I so go, disheveled and unwise, into the snowy woods with her.

(Some names have been changed – though not Mike Richmond’s, and some dates and quotes are my best guesswork.)